This resource provides instructors with an overview of accessibility in teaching and learning and general “getting started” strategies for making learning resources, tools, experiences, and opportunities accessible to all learners. Creating an accessible learning environment for your students is part of an inclusive practice. If you’re interested in learning more about inclusive teaching in general, please see the Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia.

On this page:

- What is Accessibility in Teaching and Learning?

- Why Accessibility in Teaching and Learning?

- Framework for Accessibility: Universal Design for Learning

- Getting Started

- Accessibility and Disability Statements in Syllabi

- Making In-Class Learning Accessible

- Making Online Learning Accessible

- Accessibility in Teaching and Learning at Columbia

- Additional Resources

- References

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2019). Accessibility in Teaching and Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/accessibility/

What is Accessibility in Teaching and Learning?

Learners come to our classrooms with unique sets of needs and abilities, from physical and cognitive differences to diverse socioeconomic, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds. Committing to creating accessible teaching and learning environments ensures that diverse students have equal access to educational materials, teaching methods, learning experiences, assessments, and communications from the instructors. Instructors should consider whether all learners can access the following, without barriers or restrictions:

- Materials used in teaching (for example, syllabi, textbooks, readings, presentation slides, course documents, assigned videos). Ensure that materials are accessible whether they were created or curated/selected by the instructor. If you have curated your materials from open educational resources, check that these resources are accessible as well.

- Technologies used for instruction (such as the Learning Management System CourseWorks (Canvas) or polling software like Poll Everywhere or clickers)

- Teaching methods (for example, in-class discussions, activities, lectures, hands-on experiences, assignments, and assessments)

- Learning experiences (such as field trips, community engagement activities or assignments, off-campus engagement, internships, group projects, or laboratory classes)

- Assessments (such as projects, products, papers, or performances through which students demonstrate mastery)

- Communications from the instructor (for example, in- and out-of-class communications, instructions for and feedback on assignments, expectations about in-class behavior and participation, tone of written and verbal communications)

Why Accessibility in Teaching and Learning?

Nationally, approximately 11% of undergraduates and 5% of graduate students report having a cognitive, mobility, visual, and/or auditory disability 1. Students with disabilities come to higher education with a range of previous life experiences as well as intersecting identity facets (such as race, ethnicity, gender, gender expression, socio-economic status, national origin, level and type of disability, etc.)2. Given this diversity, it is perhaps unsurprising that students with disabilities have a range of positive and negative experiences on college and university campuses. Despite the increasing emphasis on inclusion and diversity in higher education, research has consistently found that students with disabilities feel less comfortable on campus, in their departments, and in their courses than students who do not have disabilities, and they report higher rates of discrimination, bias, and hostility on campus compared to nondisabled students3. Students with disabilities report a number of barriers to their learning experiences related to receiving accommodations (for example, lack of awareness of available services, difficulty navigating policies and procedures to receive accommodations, and inadequate accommodations) and in the classroom environment (such as faculty who are uninformed about accommodations, are non-responsive to accommodations requests, or who challenge the student’s need for an accommodation) 4. Other barriers that students with disabilities face include the accessibility of physical space, negative interactions with peers, and navigating the continued stigma of disability on campuses 5. Having campus, department, and classroom climates that are welcoming, comfortable, and free from harassment, bias, and barriers to learning are an essential part of ensuring equal access to all students.

The Americans with Disabilities Act requires that universities make their programs accessible to students with disabilities, usually by making accommodations to policy, practice, or programs for individual students. At Columbia University, Disability Services works with instructors to ensure that students registered with their office receive the accommodations and support services they need to thrive as learners in their courses while preserving high academic standards. [Note: Faculty members from Barnard College, Jewish Theological Seminary, Teachers College, and Union Theological Seminary should consult their schools’ offices for students with disabilities for support. Please see Accessibility in Teaching and Learning at Columbia below for more information.] Examples of typical accommodations supported through Disability Services include allowing for more time for exams to be administered and services such as note-takers, sign language interpreters, or assistive technologies.

While you may be contacted by Disability Services on behalf of a student, and while we encourage you to take advantage of the resources that Disability Services offers, not all students seek accommodations for a disability, for a variety of reasons. True accessibiltiy emcompasses more than creating accommodations for students who have disclosed their learning needs. At the Columbia CTL, we encourage faculty and instructors to expand their thinking on accessibility beyond simply complying with federal legislation.

Having diverse students in our classrooms make the learning environments and experiences more engaging, dynamic, and rich, and result in stronger learning outcomes6. Students might vary based on their visual, auditory, cognitive, or motor abilities; they may speak a language other than English as their native language; they may have a different socio-economic status than other students or have varied levels of familial support; they may be a first-generation college or graduate student; they may have physical or mental health concerns; they may have a variety of pre-existing knowledge and experiences that make their approach to learning different from their peers’. Making teaching and learning accessible to all students is a part of good ethical practice: no student should be excluded from the learning environment, and all students should be offered the support they need to succeed.

A Framework for Accessibility: Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) provides a framework to guide the design of teaching and learning materials and experiences based on the science of learning. The idea of universal design was established in the 1960s by architects who sought to design homes and public spaces that were “usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design”7. Think about design features like curb cuts on the sidewalk, which allow people using wheelchairs, parents with children in strollers, and people pushing grocery carts to navigate the sidewalk more easily. The same logic applies when we consider how to design the learning environment to be accessible to as many learners as possible. Designing learning experiences so that a wide variety of students can access the course content, engage with course materials and learning experiences, and demonstrate their learning makes learning accessible and benefits all students, not just those who have a specific accommodation request. It helps to avoid making “one change, one time, for one person”; instead, the learning environment is designed from the outset to be as accessible as possible.

There are three principles of UDL:

- Provide multiple means of representation of course content and materials. This is the “what” of learning: what are students expected to learn, engage with, and access in order to succeed in the course?

- Provide multiple means of action and expression. This is the “how” of learning: how students will engage in different learning experiences and demonstrate what they know and what they are learning?

- Provide multiple means of engagement. This is the “why” of learning: why is the course material relevant to students and to their personal goals and motivations?

The key point to remember for applying UDL principles in the classroom is that there is not one pedagogical approach that is optimal for all learners; instructors must provide options. To learn more about Universal Design for Learning and the types of options you can offer students, please see resources listed at the bottom of this page.

Disability Accommodation and Accessibility Statements in Syllabi

Including a disability accommodation and accessibility statement in a course syllabus is one way that faculty members can convey their approach to inclusion and accessibility in the classroom. Using positive and welcoming language in accessibility statements and in your syllabus in general can demonstrate to students that you are approachable, and can influence their perceptions of the course, the faculty member, and the likelihood that they will succeed in the course8. Using inviting and positive rather than commanding and punishing language, and emphasizing cooperation and students’ agency, can empower students and create a more positive learning environment for all students9.

Standard accessibility statements include information about the legal obligations that universities and faculty members must follow and the process by which students would seek an accommodation. Statements that take a more inclusive tone signal to students that the faculty member is open to discussions about how students learn best, how the faculty member can create learning environments that are free of barriers and inclusive of all students, and that discussing diversity and inclusion is a normative practice10. More-inclusive statements also avoid singling out students with disabilities as the only students who experience barriers or need accommodations, and position the learner, faculty member, and disability services office as partners in creating an optimal learning experience for the student.

An example disability accommodation and accessibility statement is included below:

I value diversity and inclusion. I am committed to a climate of mutual respect and full participation. My goal is to create learning environments that are usable, equitable, inclusive and welcoming. If there are aspects of the instruction or design of this course that result in barriers to your inclusion, accurate assessment, or achievement, please notify me as soon as possible. Students with disabilities are also welcome to contact Disability Services to discuss a range of options to removing barriers in the course, including accommodations11.

Links to statements recommended by schools and departments at Columbia can be found below:

Making In-Class Learning Accessible

When designing in-class learning experiences, consider whether the delivery of instruction (the audio and visual components of presentations), the learning environment (the physical space as well as the general course climate), and the engagement strategies and activities used in class are accessible for as many students as possible. Consider the following:

Delivery of instruction: Present your materials in ways that are perceptible to everyone by using multiple formats (words, visual, audio). Strategies to make delivery of instruction accessible12 include:

-

- Make slides and visuals accessible to all students, including those with visual impairments or who are seated far from the screen. Use presentation slides with high-contrast between text and background and use large (24 point or larger) sans serif fonts (Arial, Verdana, Helvetica). Limit the amount of text and number of visuals on slides, and be prepared to describe visuals including images, tables, and charts. Confirm that presentation materials are visible from all parts of the room. Read more about how to design accessible presentations from the University of Washington’s DO-IT Center.

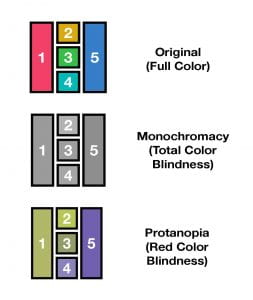

- Use graphical indicators, rather than color alone to distinguish important or meaningful material on slides or handouts. To see your web-based materials the way a student with colorblindness might, use a color-blindness simulator (for Google Chrome) or free image analyzer. If you use PowerPoint for slide presentations, use the built-in accessibility checker to check for a variety of accessibility issues that users can encounter. For more information about PowerPoint’s accessibility checker and get step-by-step instructions to resolve common accessibility issues on Microsoft’s support website. For more information about how to make documents and presentations made in Google Docs or Google Slides accessible, please see Google’s support website.

The logo for the CTL’s Guide for Inclusive Teaching uses both colors and numbers to prevent confusion for users with color blindness.

-

- Caption all videos and turn on captions when showing videos in class. Captions are helpful not just for those who have hearing impairments, but for those whose native language is different than that of the video, who are unfamiliar with technical jargon used in the video, or for listeners in loud environments13. Note: Most YouTube videos automatically generate captions, and you can turn them on or off. If you find that the captions are incorrect for videos that you own or have made, you can correct the captions following these instructions from YouTube. Professionally captioned videos will have higher rates of accuracy. Contact the CTL for recommendations on captioning.

- Include transcripts for all videos. Transcripts can help students who wish to review audio content separately from the audio or visual medium, which can also help students who have hearing impairments, language-processing impairments, or who simply want to review the material in a written rather than audio format. Note: A quick way to generate an audio transcript is to upload the audio to YouTube, download the automatically generated caption file, and then edit that file.

- Repeat students’ questions before answering, and use a microphone if available. This gives all students the chance to process spoken information during in-class lectures and discussions.

Learning environment: Make inclusion and accessibility a priority in your course by modeling accessibility best practices, and setting the expectation that students will do the same in their interactions with their peers. For example:

-

- Discuss the choices you have made to create an accessible classroom. Being open and clear with your students about your efforts to create an accessible class helps your students understand the choices you make and can help create an inclusive course climate. The language that you use around these issues can itself contribute to a positive climate.

- Assume you will teach diverse students with diverse needs. Don’t make assumptions about which students do or do not have disabilities. Be mindful that many types of disabilities or impairments may not be visible to you, and not all students with disabilities choose to seek accommodations or to disclose their disability to faculty members. If you are aware of an accomodation and have questions or concerns about it, please contact Disability Services directly.

- Get to know your students’ learning needs. Ask students to respond privately to questions like, “What would you like me to know about how you learn best?” “What can I do to support your learning needs?” or “Do you have any accessibility needs you’d like me to know about?” This not only helps you to identify potential barriers that may hinder student learning, but will help students feel supported in the classroom.

- Model person-first language. The phrase “a student with a disability” is more inclusive than “a disabled student.” Making this distinction shows that you do not define the person by their disability (also known as “person-first” language). Encourage students to use person-first language.

- Consider lifting laptop and mobile device bans. These types of prohibitions can present barriers for students with disabilities (by identifying and potentially stigmatizing them), those without accommodations who would benefit from using a device to take notes, and students who may need to stay in touch with caregivers for children or elders. Instead, discuss with students how you expect them to use technology appropriately and the cognitive consequences of distraction and multitasking. Consider how to incorporate technology into the classroom to make learning more meaningful (for example, through collaborative note-taking in a shared Google Doc). To learn more about the nuanced issues surrounding laptop bans, read the article “Enough with the Laptop Ban Debate!” from Inside Higher Ed.

- Expect that students will engage in accessibility best practices that you model. For example, require that students make their in-class presentations accessible and that they will treat all peers as valuable members of the learning community.

- Arrange furniture to ensure that all students are included (if possible). For example arrange seating so that students can interact with the instructor and each other, and move objects that may obstruct student views or space. Consider the use of space for students who use mobility devices or who may have service animals. See Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching resource on creating accessible learning environments.

Engagement strategies and course activities: Provide multiple options for students to interact with course material and to demonstrate their learning. Whenever possible, design materials, activities, and assignments to build upon students’ interests, motivations, and relevance to their lives and educational goals. For example:

-

- Design active learning activities with all learners in mind. Consider whether all students will be able to complete an activity and pay any costs associated with the course. If obstacles are anticipated, consider alternate activities that can be completed by all students successfully. Similarly, consider alternatives to out-of-class learning experiences, including extra credit opportunities, which may be inaccessible to students who have disabilities, who have family or work commitments, or who have lower incomes.

- Clarify your objectives for every assignment. When students understand the relevance of an activity for their learning they will be more motivated to engage with the assignment.

- Allow for students to have some agency in how they express their learning when possible. For example, you might allow students to choose a topic for a research paper, the mode in which they can submit the assignment (e.g., a written paper versus a podcast or video submission), or encourage students to incorporate their own interests and cultural backgrounds into their course materials.

Making Online Learning Accessible

When curating or creating your own learning materials, setting up your CourseWorks (Canvas) site, or using digital tools, consider the points below. These recommendations take into consideration students who encounter your online materials using technology you may not anticipate, such as a screen reader, or who do not have easy access to the most up-to-date devices.

- Content within CourseWorks (Canvas) needs to be accessible for all students, whether or not the content was created or designed by the faculty member. Use the Accessibility Checker in CourseWorks (Canvas) to verify that the content you create is accessible, and refer to the General Accessibility Design Guidelines created by Canvas.

- Many of the same techniques used to ensure that in-person course materials are accessible apply to those delivered online. Some accessibility concerns are particular to hybrid and online-only courses. See the above section on delivery of instruction for general suggestions, and the following tips specific to hybrid or online-only classes:

- Use consistent layouts and organizational schemes to present content, and make the organizational system transparent to students. This can serve as a road map for the course, and help students understand where they have been and where they are going in terms of their learning.

- Use headings and paragraph style features and built-in slide designs and layouts whenever possible, and avoid using bolded text as a replacement for headers 14. Screen readers rely on these headings and layouts to determine the order in which elements are read and for navigation through documents and slides. Without them, documents read as one single section.

- Embed hyperlinks within other text and use descriptive wording for hyperlinks (e.g., “Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning” rather than text such as “click here” or the full URL such as “ctl.columbia.edu”). This makes the destination of the link clear to all students, and makes the links easier to scan, find, and use for students using a screen reader. An exception to this rule is when listing email addresses; in that case, type out addresses rather than embedding them (e.g., “ctlfaculty@columbia.edu” rather than “CTL Faculty”) because screen readers may not recognize the descriptive text as an email address.

- Captions assist students with audio processing issues and those listening in their non-native language.There are a variety of ways to generate captions for video. YouTube automatically generates captions, but they are not always accurate. You can manually correct the caption file for accuracy.

- Transcripts can help students who wish to review audio content separately from the audio or visual medium. A way to quickly generate an audio transcript is to upload the audio to YouTube, download the automatically generated caption file, and then edit that file.

- Alt-text helps students accessing your material with a screen reader understand what images are on the page. Most software programs that allow images to be embedded also allow you to create alt-text associated with the image. In CourseWorks (Canvas), the “embed image” dialog box gives a space for alt-text, as does PowerPoint. Please refer to the resource Image Alt-Text from Accessibility Penn State for best practices related to alt-text.

Accessible file formats ensure that files are available for students who may not have access to or who cannot use some software packages. Formats that are generally accessible are: .pdf for documents, .jpeg for images, .mp3 for audio, and .mp4 for video. Note: For text documents, we recommend offering files in two formats (.pdf and as a Word document) because some document formats cannot be accessed by all screen reading software (used by students with visual impairments to read documents aloud).

Accessibility in Teaching and Learning at Columbia

Disability Services facilitates equal access for Columbia students with disabilities by coordinating accommodations and support services across both Morningside and the Columbia University Irving Medical Center campuses. Disability Services does not offer support for students at affiliated schools; please see the following pages for more information about support for students with disabilities at those colleges.

- Center for Accessibility Resources & Disability Services, Barnard College

- Students with Disabilities, Jewish Theological Seminary

- Office of Access and Services for Individuals with Disabilities, Teacher’s College

- Disability Services, Union Theological Seminary

Please consult the Faculty Guide for Disability Services and Teaching Students with Disabilities for more information about accommodations and how faculty members can support students with accommodations.

The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning offers the following resources and support for faculty and graduate students from all Columbia-affiliated colleges and schools who want to expand their accessible and inclusive teaching practices:

- The online resource Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia, see Principle 4: Design all course elements for accessibility.

- The self-paced ColumbiaX online course Inclusive Teaching: Supporting All Students in the College Classroom; and

- One-on-one consultations on Universal Design for Learning as it applies to the design of courses, learning materials, learning experiences, assessments, and CourseWorks (Columbia’s Learning Management System).

Additional Resources

LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda.com) course “Teaching Techniques: Making Accessible Learning” (access using your UNI log in). This online course provides a basic overview of what is accessible learning and how to make learning accessible.

Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction. DO-IT (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology, University of Washington) provides a process for making instruction accessible.

UDL on Campus, CAST, is a website devoted to resources on Universal Design for Learning in Higher Education. Learn about applying UDL to course design, the use of technology and digital media, and ways to ensure that learning opportunities are inclusive of all.

References

Bates College. “Sample Syllabus Accessibility Statement.” n.d. Accessed from https://www.bates.edu/accessible-education/faculty/sample-syllabus-statement/.

Burgstahler, Sheryl. University Design in Higher Education: From Principles to Practices. Second Edition. Harvard Education Press, 2015.

Burgstahler, Sheryl. “Equal Access: Universal Design of Your Presentation.” University of Washington DO-IT Center, 2017. Accessed from https://www.washington.edu/doit/equal-access-universal-design-your-presentation

CAST. “UDL on Campus.” CAST.org, 2018. Accessed from http://udloncampus.cast.org/page/udl_gettingstarted#.XFB5Ys9KjBI

Gurin, Patricia, Eric L. Dey, Sylvia Hurtado, and Gerald Gurin. “Diversity and Higher Education: Theory and Impact on Educational Outcomes.” Harvard Educational Review 72, 3 (Fall 2002): 330-366.

Harbour, Wendy. S., and Greenberg, Daniel. “Campus Climate and Students with Disabilities.” NCCSD Research Brief, 1:2 (2017). Huntersville, NC: National Center for College Students with Disabilities, Association on Higher Education and Disability. Accessed from http://www.nccsdonline.org/uploads/7/6/7/7/7677280/nccsd_campus_climate_brief_-_final_pdf_with_tags2.pdf

Meyer, A., Rose, D.H., and Gordon, D. Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST, 2013.

Morris, Karla Kmetz, Casey Frechette, Lyman Dukes III, Nicole Stowell, Nicole Emert Topping, and David Brodosi. “Closed Captioning Matters: Examining the Value of Closed Captions for All Students.” Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability 29, 3 (2016): 231-238.

Refocus: Viewing the Work of Disability Services Differently. “Syllabus Statement.” Accessed from http://exploreaccess.org/projectshift-refocus/syllabus.htm.

Scott, Sally. “Access and Participation in Higher Education: Perspectives of College Students with Disabilities.” NCCSD Research Brief 2, 2 (2019). Huntersville, NC: National Center for College Students with Disabilities, Association on Higher Education and Disability. Accessed from http://www.nccsdonline.org/uploads/7/6/7/7/7677280/na_focus_groups_research_brief_final_pdf.pdf

Slattery, Jeanne and Janet F. Carlson. “Preparing an Effective Syllabus: Current Best Practices.” College Teaching 53, 4 (2005): 159-164.

Tulane University. “Accessible Syllabus Project.” 2015. Accessed from https://www.accessiblesyllabus.com/.

University of Minnesota Disability Resource Center. “Accessible U.: Core Skills,” 2019. Accessed from https://accessibility.umn.edu/core-skills/headings.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. “Characteristics and Outcomes of Undergraduates with Disabilities.” 2017. Accessed from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018432.pdf

The Universal Design Project. “What is Universal Design?” 2019. Accessed from https://universaldesign.org/definition

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. “Characteristics and Outcomes of Undergraduates with Disabilities.” 2017. Accessed from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018432.pdf ↩

- Harbour, Wendy. S., and Greenberg, Daniel. “Campus Climate and Students with Disabilities.” NCCSD Research Brief, 1:2 (2017). Huntersville, NC: National Center for College Students with Disabilities, Association on Higher Education and Disability. Accessed from http://www.nccsdonline.org/uploads/7/6/7/7/7677280/nccsd_campus_climate_brief_-_final_pdf_with_tags2.pdf ↩

- Harbour and Greenberg, 2017 ↩

- Scott, Sally. “Access and Participation in Higher Education: Perspectives of College Students with Disabilities.” NCCSD Research Brief 2, 2 (2019). Huntersville, NC: National Center for College Students with Disabilities, Association on Higher Education and Disability. Accessed from http://www.nccsdonline.org/uploads/7/6/7/7/7677280/na_focus_groups_research_brief_final_pdf.pdf ↩

- Scott, 2019 ↩

- Gurin, Patricia, Eric L. Dey, Sylvia Hurtado, and Gerald Gurin. “Diversity and Higher Education: Theory and Impact on Educational Outcomes.” Harvard Educational Review 72, 3 (Fall 2002): 330-366 ↩

- The Universal Design Project. “What is Universal Design?” 2019. Accessed from https://universaldesign.org/definition ↩

- Slattery, Jeanne and Janet F. Carlson. “Preparing an Effective Syllabus: Current Best Practices.” College Teaching 53, 4 (2005): 159-164. ↩

- Tulane University. “Accessible Syllabus Project.” 2015. Accessed from https://www.accessiblesyllabus.com/ ↩

- Bates College. “Sample Syllabus Accessibility Statement.” n.d. Accessed from https://www.bates.edu/accessible-education/faculty/sample-syllabus-statement/ ↩

- Adapted from Refocus: Viewing the Work of Disability Services Differently. “Syllabus Statement.” Accessed from http://exploreaccess.org/projectshift-refocus/syllabus.htm ↩

- Burgstahler, Sheryl. “Equal Access: Universal Design of Your Presentation.” University of Washington DO-IT Center, 2017. Accessed from https://www.washington.edu/doit/equal-access-universal-design-your-presentation ↩

- Morris et al. “Closed Captioning Matters: Examining the Value of Closed Captions for All Students.” Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability 29, 3 (2016): 231-238. ↩

- University of Minnesota Disability Resource Center. “Accessible U.: Core Skills,” 2019. Accessed from https://accessibility.umn.edu/core-skills/headings ↩