On this page:

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Peer Review: Intentional Design for Any Course Context. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/peer-review/

The What and Why of Peer Review

Peer review, as the name suggests, is the act of receiving feedback from a colleague or classmate. It typically happens throughout the course of a written assignment, perhaps at the halfway point, and often involves classmates commenting and providing feedback on each other’s work in any number of formats. There might be specific questions or prompts provided by the instructor, or the activity may be based on the writer’s specific concerns.

The process of peer review can help students make purposeful and intentional choices in their own work by offering their perspective and insight to their peers. It also gives students an opportunity to see how others have responded to a similar prompt, text, or assignment, which can help their own understanding of the topic or assignment grow. In their research on the benefits of peer review, Ambrose et al. (2010) demonstrate how the peer review process has mutual benefits for “readers, writers, and instructors alike” (pp. 257). For readers, peer review can help them re-see their own work. For writers, the feedback gained in peer review can help focus the revision process. Finally, instructors also benefit because they receive work that has already undergone at least one round of feedback and revision. Research has shown that students who receive focused feedback from at least four peers have better revision than those who received instructor feedback only (Ambrose et. al, 2010, pp. 257). Thus, it is important to have clear processes and expectations for peer review, as well as multiple opportunities available throughout a course.

Considerations for Successful Peer Review Design and Implementation

When planning peer review activities, it is important for instructors to consider the overall assignment learning objectives, scaffolded in-class activities, peer review expectations, and the goals of peer review for students. With the various components of the assignment in mind, designing peer review activities will be more intentional and can further support students’ success on a given assignment.

| Designing Peer Review Activities | |||

| 1. | Align the peer review activity with the learning objectives for the writing assignment. | ||

| 2. | Design peer review activity with all elements of writing in mind. (e.g.: necessary prep work, timing of the activity, time for feedback implementation) | ||

| 3. | Model expectations. (e.g.: demo of peer review with students) | ||

| 4. | Identify a clear assessment plan for peer review activities and share that with students. | ||

| 5. | Determine platform(s) or tool(s) needed for your context. | ||

| In-person | Hybrid (HyFlex) | Online | |

|

– Small groups in class – Collaborative doc – CourseWorks |

– Breakout rooms – Collaborative doc – CourseWorks |

– Breakout rooms – Collaborative doc – CourseWorks |

|

1. Align the peer review activity with the learning objectives for the writing assignment.

What are the goals for the peer review activity, and what parts of the assignment do they align with? What questions or concepts will students address in the activity?

Aligning peer review activities with the learning objectives of the assignment can help students strengthen their connections and understanding of assignment expectations. This alignment can also help target feedback so that students are focusing on the parts of the assignment they need to be successful. Early opportunities and activities that ask students to provide targeted feedback (e.g.: concrete suggestions and examples) allows them to practice the skills identified in the assignment learning objectives and may help them identify similar writing needs in their own work. Lastly, providing students with a guided peer review activity can help offset surface-level comments (e.g.: “This looks good!”) or an over-focus on line-by-line copyediting.

2. Design the peer review activity by considering all elements of the writing assignment.

When will students receive peer feedback versus instructor feedback? What in-class activities will students have completed prior to peer review?

Think about the moments of intervention throughout the assignment and how each of these moments might build upon the next. This can help you scaffold students’ feedback throughout the assignment, as well further align class activities and learning objectives. It’s also important to consider what students will need to prepare for the peer review activity: what will you ask them to share during the activity? How much of their draft should they bring for peer review? Lastly, be clear with students about your expectations for timing: What amount of synchronous or in-class time will students have for the activity? What will the out-of-class expectations be? When deciding how much time you allot, be mindful of students’ different learning preferences and language experiences.

3. Model your expectations for successful peer review.

What does successful peer review look like in your class? How will students know what the expectations are?

As John Bean (2011) notes, “Unless the teacher structures the sessions and trains students in what to do, peer reviewers may offer eccentric, superficial, or otherwise unhelpful–or even bad–advice” (pp. 295). One way you might train students is to engage them in whole-class peer review using a sample paper. There is no way to know what students’ previous peer review experiences have been, so offering a whole class model can help establish expectations early on. You can also partner with your students to create clear peer review guidelines, helping students learn how to evaluate each other’s work. Additionally, you might choose to share your own experiences with peer review with your students. Reflect upon what kinds of feedback you found most and least helpful, and share that with students, and even invite them to join that reflection and discussion. This can serve as a springboard for a conversation about your class peer review expectations.

4. Identify a clear assessment plan for peer review activities, and share that with students.

Will you assess students’ participation and contributions? If so, what will that look like? If you assess peer review, how will you help students develop those skills? (See item 3 above.)

If you decide to assess students’ peer review participation, be sure to have clear conversations about these expectations with students. You might refer to established peer review guidelines (discussed above). If you have a rubric for the assignment, you might also consider if peer review is a part of that rubric. Or, you might encourage students to use the assignment rubric as a peer review activity and assess students’ engagement with the rubric. Lastly, peer review activities present a great opportunity for a low-stakes assessment in the classroom, which are known to reduce student anxiety and increase students’ confidence in their work (Lang, 2013).

5. Determine the platform or tool that will help facilitate peer review.

What platform(s) or tool(s) will best help facilitate the peer review activity? What level of instruction or preparation will students need prior to engaging in the activity?

While sharing hard-copies of drafts is a common practice for in-person class meetings, there are a number of different ways students can engage in online peer review. After determining the appropriate activity based on the learning objectives and students’ needs, choosing the right tool or platform can ensure that students are able to achieve the goals of the activity. Read on to learn about platform or tool considerations.

Instructional Technologies to Support Peer Review

Zoom Breakout Rooms, Google Docs, and CourseWorks (Canvas) can be used to help facilitate peer review. Find the platform or tool that will work best for your course context. Need assistance? Contact the CTL at ColumbiaCTL@columbia.edu.

Zoom Breakout Rooms

Zoom breakout rooms can be used during synchronous class sessions to simulate the small group discussions that may take place during in-class peer review. You can pre-assign students in peer review pairs or groups, or you can assign students randomly in the moment. With pre-assignments, you will want to consider if students will remain in the same peer review groups throughout the semester or if you’ll switch groups up across assignments. Additionally, will students be asked to read each other’s work ahead of the breakout room activity? If so, be sure to provide explicit expectations about what students should address and do in preparation for and during the peer review activity.

See Zoom Help Center “Enabling breakout rooms;” “Manage breakout rooms;” and “Pre-assign participants to breakout rooms.”

Google Docs

Google Docs are a great tool for synchronous and asynchronous peer review. They are also particularly useful if you are planning to assess students’ peer review participation. Google Docs can be a valuable peer review facilitation tool, regardless of classroom format; whether in-person or online, synchronous or asynchronous, they can be used to help students foster their feedback skills.

For synchronous class sessions or face-to-face classes, you might pair the Google Doc with small group peer review, either in-class or via Zoom breakout rooms. Students could be working in the same collaborative writing space while also talking with each other about their work and comments they are making. As the instructor, you can see students’ comments and feedback in real time, even if you do not join the breakout room discussions.

Asynchronously, or for work done outside of a face-to-face course, you might ask students to share their work with each other and leave comments and feedback throughout the document. Students can respond to questions and comments left on the document, and the reviewers will be notified, prompting a dialogue. Additionally, there is a chat function within Google Docs, so two or more students, if working in the document at the same time, could ask questions and talk via chat. You may even consider pairing an asynchronous peer review activity with a brief in-class activity between pairs/groups.

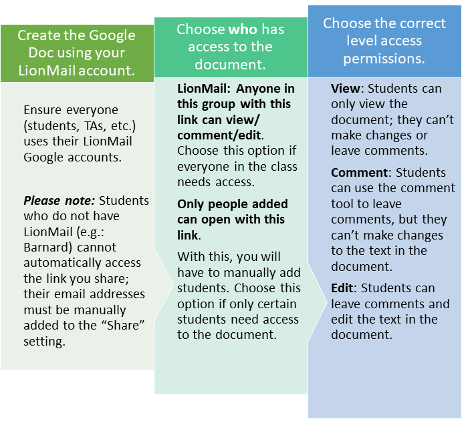

Creating and Sharing a Google Doc: Settings and Permissions Considerations: When using Google Docs, there are some important considerations related to sharing settings and access. The image below includes some of these steps and considerations; for more about sharing within LionMail, see CUIT’s LionMail (Google) Drive help page.

CourseWorks (Canvas)

You can use CourseWorks to facilitate peer review activities through a number of tools. Two of the most common ones include the Peer Review Function and the Discussions Tool.

Peer Review Function: As its name suggests, the peer review function in CourseWorks allows the instructor to assign student work to others for review. This function is particularly useful in large classes (50+) as it helps manage the logistics of assigning peer review groups. It is also useful if you want to assign specific papers or work to specific students, or if you want the option for anonymous peer review comments. Any assignment you create in CourseWorks can be assigned to peer review; once selected, you can manually assign students work to peer review, or CourseWorks can randomly allocate the papers.

For more detailed information on assigning Peer Review in CourseWorks visit the Canvas help documentation.

Discussions Tool: The Discussions tool allows students to easily share their work with each other. They can post their work as an attachment to a discussion post, (e.g. Word document, PDF) or by sharing a Google Doc link in the post itself. Because of its availability to the entire class, the Discussions tool is particularly useful when you want the whole class to see peers’ work, or if the number of viewers does not matter. If you would like to limit the view to only a number of select students, you can also assign a Discussion to a group of students and only those in that particular group will see the posts.

No matter the use of the Discussions tool, whether through the whole-class or for select groups, it’s important to provide clear instructions that articulate the peer review goals and activity, as well as your expectations, for students. For instructions on how to create Discussion posts, visit the Canvas help documentation.

Columbia Resources

CTL Knowledge Base

CTL Office Hours and Support

Writing Centers provide various services to support students and their writing. They are a great resource for students’ to get additional feedback and support throughout the writing process, whether at the initial brainstorming stage or as students work to implement peer or instructor feedback.

Barnard Writing Center

Columbia Writing Center

Columbia School of Social Work Writing Center

Teachers College Graduate Writing Center

References

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M.C., & Norman, M.K. (2010). What is reader response/peer review and how can we use it? In S.A. Ambrose et al. How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching (pp. 257-9). Jossey-Bass.

Bean, J. C. (2011). Have students conduct peer reviews of drafts. Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom, 2nd Edition (pp. 295-302). Jossey-Bass.

Lang, J.M. (2013). Cheating lessons: Learning from academic dishonesty. Harvard University Press.

Science Education Resource Center (SERC) at Carleton College. (n.d.). Guidelines for students – peer review. Pedagogy in Action: the SERC Portal for Educators.

Additional Resources

Salahub, J. (1994-2020). Peer review. The WAC Clearinghouse. Colorado State University.

University of Michigan Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (CRLT). (n.d.). Feedback on student writing. CRLT.