Contemplative Pedagogy

Introduction

Contemplative Pedagogy is an approach to teaching and learning with the goal of encouraging deep learning through focused attention, reflection, and heightened awareness. Learners are encouraged to engage deeply with course material through contemplation and introspection (examining their thoughts and feelings as related to the classroom content and their learning experiences). In their foundational text Contemplative Practices in Higher Education, Barbezat and Bush note that as students “find more of themselves in their courses,”1 they will make meaningful and lasting connections to their learning.

Regardless of discipline and educational context, contemplative techniques can complement more traditional classroom activities to transform the way students come to learn about and understand the world. Many of the activities that instructors already use in the classroom–writing, close reading, reflection–may be intentionally (re)designed to draw more on contemplative practices and principles.

On this page:

The CTL is here to help!

For additional support with incorporating contemplative pedagogy into your course, email CTLFaculty@columbia.edu to schedule your 1-1 consultation.

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2017). Contemplative Pedagogy. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/contemplative-pedagogy/

Why Use Contemplative Pedagogy?

Instructors and learners alike deal with a multitude of distractions, demands on their time, anxieties about teaching and learning, and the pressure to multitask. There are a variety of teaching and learning challenges that one may encounter which can be addressed by contemplative pedagogical practices, including: student distraction or anxiety, superficial learning, rigid thinking, inability to see how course material relates to students’ daily lives, and students who are motivated by grades, rather than by learning.

The integration of contemplative practices encourages instructors and learners to focus on the present moment, to fully engage in teaching and learning, and to achieve focus and attention in the classroom. As Barbezat and Bush2 note, “Professors find that not only are students better able to be present in the moment with the subject matter and each other, but they are better able to hold on to what they are learning over time and integrate it into meaningful patterns.” Contemplative practices can help students tap into their emotional reaction to course materials and to confront difficult course topics, allowing them to engage more openly and holistically with the course material and their peers in the class.

Contemplative methods expand the traditional focus of teaching and learning to include:3

- Focus and attention building: Learning is enhanced as students are attentive to what and how they are learning.

- Deeper understanding of and connection to course materials: Learning becomes more meaningful and relevant as students reflect upon course material and make connections to their experiences.

- Compassion and connection to others: Learners develop empathy and interpersonal connection.

- Self-inquiry, personal meaning, and creativity: Learners engage in a process of self-inquiry to deepen their relationship to their learning, tap into their creativity and insight, and develop more awareness about their own learning processes.

Instructors can build in opportunities for students to develop deeper understandings of course material by giving them time to reflect on what they are learning, how they are learning (i.e., their learning process), and by making connections between their own experiences and course material.

Practices

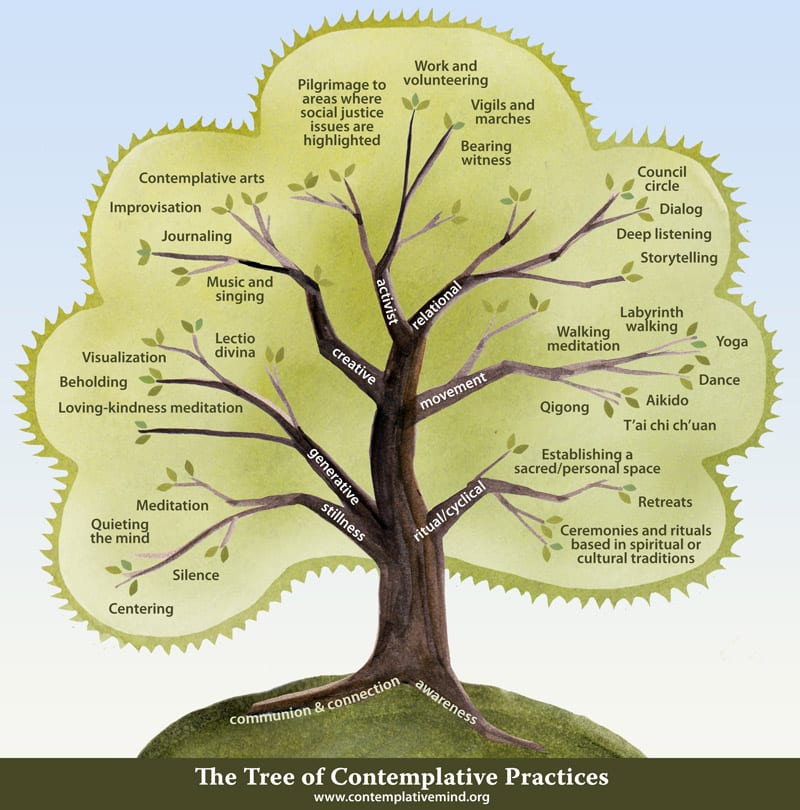

There is a spectrum of contemplative practices available, as illustrated by the Tree of Contemplative Practices from the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. Each branch represents a different category of practices that align with the root intentions of contemplative practice (awareness and connection). Below are several examples of practices that have been described in the contemplative pedagogy literature. Note: these practices can be integrated into classrooms across disciplines and institutional contexts.

Click on the toggles below to learn more about practices for mindfulness meditation, beholding, contemplative reading, and contemplative writing.

Mindfulness Meditation

Addresses Common Teaching & Learning Challenges:

- “My students are distracted and unfocused in class.”

- “How can I help create a supportive class climate?”

- “My students are anxious about their performance in class.”

Purpose:

- Focus and attention building

- Compassion and connection to others

Time: Varies; as little as 3-5 minutes

Implementation:

- Sit in silence (eyes closed or soft focus)

- Focus on the breath

- Observe thoughts, but don’t engage or judge them; allow them to flow

- Select an object of concentration (e.g. breath, question, idea, guided visualization)

Examples: Breath awareness; contemplation on a question or concept; transition between activities or at start of class; reflection before or after difficult topics, before presentations, or before quizzes or exams.

Beholding

Addresses Common Teaching & Learning Challenges:

- “My students have been learning in superficial ways.”

- “How do I help my students take notice of nuance/detail in the material presented?”

- “I want to help my students develop new perspectives on a topic.”

- “How can I stimulate my students’ creativity and imagination?”

Purpose: Deeper understanding and connection to course-related images and objects; self-inquiry, personal meaning, and creativity in relation to images and objects

Time: Varies; at least 10-15 minutes

Implementation: From Joel Upton9

- Select an object or image to observe

- Gather basic information about the work

- Analyze form, shape, and color with full attention

- Explore content, iconography, and symbolism

- Identify contradictions and conflicting elements

- Behold the work

Contemplative Reading

Addresses Common Teaching & Learning Challenges:

- My students struggle to understand difficult texts.

- My students do not remember what they read.

- Students complain that they don’t see the relevance of course readings.

Purpose: Focus and attention building; Deeper understanding of and connection to course materials

Time: Varies

Implementation: Immersive, attentive, slow, done in community / in dialogue with text and others

Example: Reading aloud, in-class or as homework; use of digital media in conjunction with traditional texts; slow reading, rereading, annotating, performing, or memorizing passages.

Contemplative Writing

Addresses Common Teaching & Learning Challenges:

- How can I help my students overcome writer’s block and procrastination?

- My students are very grade-motivated, rather than learning-motivated.

- I want my students to reflect on how class experiences relate to their everyday lives.

Purpose: Deeper understanding of and connection to course materials; self-inquiry, personal meaning, and creativity

Time: Varies; generally ranges from 5-20 minutes

Implementation: Varies depending on technique.

Examples:

- Mindful writing: Use a few moments of reflection/contemplation before, during, or after writing to clarify and refine thoughts.

- Freewriting: Write continuously (without stopping to fix grammar, spelling, etc.) for a predetermined amount of time (10-15 minutes). Prompts can be based on a specific question, more general (e.g., “when I read the text, I thought…”) or by asking students to incorporate a specific word.

- Journaling: students write about their experience (usually a paragraph or two) from a first-person perspective. Students sometimes benefit from more structured experience; for example, using their journal to address a specific prompt.

How Do I Get Started?

Consider the following to guide your planning and implementation of contemplative practices 15:

Planning – to do outside of the classroom:

- Familiarize yourself with contemplative pedagogical practices; consider researching the historical and cultural context of a practice, or experiencing the practice yourself prior to implementing in class. This will allow you to guide your learners through the practice, and help them process the experience.16

- Start small: Make small tweaks to your pedagogical approach that are are intentional and aligned with desired learning. Introducing small changes can be more manageable than making large-scale changes to your courses, and many of these small changes can take place in the moments before class starts, in the first and last few minutes of class, and as a transition between class activities.17 For instance, open a class session with a mindfulness exercise (free writing, breathing) to focus student attention and prepare them for learning, or use contemplative writing at the end of class to encourage students to reflect on what they learned that day.

- Have a clear pedagogical purpose for the practice, so that you can lead the session toward the goal and properly assess its impact.

- Plan the structure of the practice selected, but allow for flexibility and improvisation so you can be responsive to students in the moment.

- Time the activity appropriately (e.g., start-of-class, mid-class, end-of-class).

Implementation – to do inside the classroom:

- Be intentional and transparent with students so that they understand the purpose of the practice and how it relates to their learning.

- Articulate the purpose to your students so they are open to participating in the practice.

- Contextualize it in the course so that students understand how it is affecting their learning.

- Provide an opportunity for students to opt out during any practice (and complete an alternative activity) so students feel safe in exploring it.

- Allow students time after the exercise to reflect on and write about their experience. If appropriate, give students an opportunity to discuss their experiences with each other.

Note: Many contemplative practices have cultural and religious foundations, and it’s important to acknowledge these. Instructors who wish to adopt contemplative practices in the classroom should do so with a mindset toward openness and inclusion. Practices which draw upon evidence-based practices and the science of teaching and learning rather than religious practice can help students achieve high levels of attention, focus, and insight without causing alienation, exclusion, or discomfort. Whenever possible, instructors should strive to understand the origins of the practices they are incorporating into their courses, and should provide an appropriate amount of context about the history of the practice for students.

References

Bach, D. J., & Alexander, J. (2015). Contemplative Approaches to Reading and Writing: Cultivating Choice, Connectedness, and Wholeheartedness in the Critical Humanities. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 2(1).

Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons.

Corrigan, P. T. (2013). Attending to the Act of Reading: Critical Reading, Contemplative Reading, and Active Reading. Essays in Reader-Oriented Theory, Criticism, and Pedagogy, 63(2012), 146.

Haynes, D. (2010). Contemplative Practice: Views from the Religion Classroom and Artist’s Studio. In Arthur, R. J. (ed). Working Bibliography of Teaching and Learning Publications and Presentations related to the Work of the Wabash Center by Wabash Center Participants and Grant Recipients. Teaching Theology & Religion, 15(1), 72-83.

Lang, James. (2016). Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning. Jossey-Bass.

Shapiro, S. L., Brown, K. W., & Astin, J. A. (2008). Toward the integration of meditation into higher education: A review of research. The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. Retrieved from http://www.contemplativemind.org/admin/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/MedandHigherEd.pdf

Additional Reading

The following articles are recommended as foundational to an understanding of contemplative pedagogy:

Hart, T. (2004). Opening the contemplative mind in the classroom. Journal of transformative education, 2(1), 28-46.

Zajonc, A. (2013). Contemplative pedagogy: A quiet revolution in higher education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2013(134), 83-94.

Resources

Columbia Resources

Columbia offers some wellness resources for students, faculty and staff to receive counseling support and additional opportunities to explore mindfulness practices.

Office of Work/Life Mindfulness Programs are available for staff and faculty interested in developing their skills with meditation. Programs are offered each semester at CUMC.

Columbia Health – Alice Health Promotions provides mental health and wellness programs to students, faculty and staff.

CUMC Center for Student Wellness provides health and wellness programs and resources for students to maximize personal and professional development.

Higher Education Resources

Many universities are exploring and integrating contemplative pedagogy into their research and curricula. Below is a list of centers and organizations that engage in this work, publish and maintain resources to help you explore contemplative pedagogy.

The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society is an organization dedicated to promoting the use of contemplative pedagogy in higher education. This site has a large collection of resources, publications, and programs that are focused on contemplative pedagogy. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry is a peer-reviewed journal published by the center.

The Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, was founded in 1979 by Jon Kabat-Zinn, the developer of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction. This site is filled with research and resources into the use of mindfulness-based intervention, particularly for use in healthcare fields.

The Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education at the Stanford University Medical School, has a wealth of research, resources, and engaging videos with a focus on compassion.

Greater Good in Action is a collection of research-based methods to cultivate a happy and meaningful life, presented by UC Berkeley.

Footnotes

- Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons, 9 ↩

- Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons, 96 ↩

- Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons. ↩

- Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons, 95 ↩

- Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons. ↩

- Shapiro, S. L., Brown, K. W., & Astin, J. A. (2008). Toward the integration of meditation into higher education: A review of research. The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. Retrieved from http://www.contemplativemind.org/admin/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/MedandHigherEd.pdf ↩

- Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 95-109 ↩

- Haynes, D. (2010). Contemplative Practice: Views from the Religion Classroom and Artist’s Studio. In Arthur, R. J. (ed). Working Bibliography of Teaching and Learning Publications and Presentations related to the Work of the Wabash Center by Wabash Center Participants and Grant Recipients. Teaching Theology & Religion, 15(1), 72-83. ↩

- as cited in Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons, p 152 ↩

- Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 111-122 ↩

- Bach, D. J., & Alexander, J. (2015). Contemplative Approaches to Reading and Writing: Cultivating Choice, Connectedness, and Wholeheartedness in the Critical Humanities. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 2(1). ↩

- Corrigan, P. T. (2013). Attending to the Act of Reading: Critical Reading, Contemplative Reading, and Active Reading. Essays in Reader-Oriented Theory, Criticism, and Pedagogy, 63(2012), 146. ↩

- Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 123-135 ↩

- Bach, D. J., & Alexander, J. (2015). Contemplative Approaches to Reading and Writing: Cultivating Choice, Connectedness, and Wholeheartedness in the Critical Humanities. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 2(1). ↩

- Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons. ↩

- Barbezat, D. P., & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons. ↩

- Lang, James. (2016). Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning. Jossey-Bass. ↩