Community Building in the Classroom

What is community building and why is it important? How do I build community in my class? This research-informed guide addresses these questions with a particular focus on synchronous community building strategies. At the same time, many of the community building strategies presented in this guide can also be adapted to the asynchronous modality. Considerations for asynchronous engagement are outlined at the end of the guide.

The CTL is here to consult with instructors on further exploring community building strategies. To schedule your one-on-one consultation, please contact the Faculty Programs and Services team at CTLfaculty@columbia.edu.

On this page:

- What is Community Building?

- Why Build Community?

- Community Building Strategies

- Social Icebreakers

- Metacognitive Activities

- Content-based Activities

- Considerations for Asynchronous Modality and Large Courses

- References

The CTL is here to help!

For additional support with community building in your course, email CTLFaculty@columbia.edu to schedule your 1-1 consultation.

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Community Building in the Classroom. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/teaching-with-technology/teaching-online/community-building/

What is Community Building?

A community is a supportive social group in which members feel a sense of belonging and share a common interest, experience, or goals (Berry, 2017; Brown, 2001; McMillan & Chavis, 1986; Rovai, 2003). Particularly in a learning community, members (both students and instructors) engage in collective inquiry and provide each other with academic and social support (Lai, 2015; Shrivastava, 1999).

Community building in the classroom is about creating a space in which students and instructors are committed to a shared learning goal and achieve learning through frequent collaboration and social interaction (Adams & Wilson, 2020; Berry, 2019; McMillan & Chavis, 1986). With intentional planning and deliberate pedagogical choices, cultivating and reinforcing positive interactions among classroom participants becomes an essential component of building a classroom community.

Why Build Community?

Community building is vital to active student engagement in a course across all modalities. Research shows that when students feel that they belong to their academic community, that they matter to one another, and that they can find emotional, social, and cognitive support for one another, they are able to engage in dialogue and reflection more actively and take ownership and responsibility of their own learning (Baker, 2010; Berry, 2019; Brown, 2001; Bush et al. 2010; Cowan, 2012; Lohr & Haley, 2018; Sadera et al., 2009).

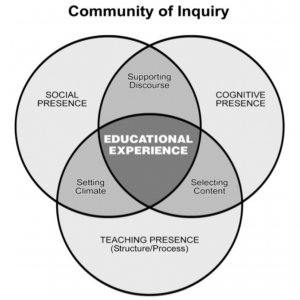

In particular, the community of inquiry (CoI) framework (Garrison, 2009; Garrison et al., 2010) is widely noted for its three elements – social presence, teaching presence, and cognitive presence – that are deemed critical for fostering a community of actively engaged participants.

The interplay of the social presence (participants’ ability to establish themselves as real/authentic selves in their academic community), cognitive presence (participants’ ability to construct meaning and confirm understanding), and teaching presence (instructor’s ability to design, facilitate, and provide direct instruction) cultivates a community that provides optimal support for student learning. Deliberate community building is therefore a key component of successful student engagement and performance in class.

Community Building Strategies

This section provides community building strategies that are organized in three broad categories: social icebreakers, metacognitive activities, and content-based activities. These strategies are presented as suggestions and are not meant to be prescriptive; adapt and modify these example activities according to your unique teaching context.

To ensure the successful implementation of community building strategies in your course, consider your context, the technologies available to you and your students, and what must be prepared and established prior to students interacting and collaborating with each other as a whole class or in small groups (see checklist below).

In this short video, learn more about creating community agreements in the classroom, as part of the CTL’s “Teaching Talks” initiative.

| Preparing for community building in class | |

| Set up community agreements to establish mutual expectations for participating in whole class interaction (e.g., taking turns to speak, actively listening to others) | ✓ |

| Check the technology in advance (e.g., microphones, speakers, cameras, polling tools, online collaborative documents, video-conferencing platforms). Ensure that the features you plan to use are enabled and are working. | ✓ |

| When setting up small group interactions, consider asking students to have their earphones and electronic devices ready in case they need to use their individual devices for their group activity. | ✓ |

| Have contact information of classroom tech support handy so that you can request technical help when needed. | ✓ |

Social Icebreakers

What are social icebreakers? Social icebreakers are instructional tactics designed to facilitate rapport building with students, foster a safe learning environment, and relieve inhibition or tension in the class (Chlup & Collins, 2010; Fisher &Tucker, 2004; McGrath et al., 2014).

Why would I use social icebreakers? What do they achieve? Through icebreakers, students are able to not only warm up to each other but also familiarize themselves with the technological tools or platforms that you might often use in your class (e.g., discussion boards, polls, collaborative documents, etc.). When the anxiety of being in a new class environment with new classmates eases, students are more willing to participate in class and actively engage in learning.

When would I use social icebreakers? Social icebreakers often occur at the beginning of the semester, but they need not only be a one-time event on the first day of class. In fact, using icebreakers at various times throughout the course would allow students to continue the community building process and allow for more substantive interaction among themselves.

Sample activities

| Interviews |

(Barkley et al., 2014, p. 59) |

| Connections |

(Barkley et al., 2014, p. 60) |

| Soundtrack of your life |

(Dunlap & Lowenthal, 2010, p. 62) |

| Where are you from? |

(McGrath et al., 2014) |

| Your favorite quote |

(Chlup & Collins, 2010) |

Metacognitive Activities

What are metacognitive activities? Metacognition refers to knowledge about one’s own thoughts, including the cognitive process and regulation involved in directing one’s learning (Ambrose et al., 2010; Akyol & Garrison, 2011; Dunlosky & Medcalfe, 2009; Lai, 2011). Metacognitive activities (e.g., self-assessment, self-explanation, monitoring, revising, etc.) allow students to reflect on and regulate their own learning. For a more detailed explanation, see the CTL resource on Metacognition.

Why would I use metacognitive activities? What do they achieve? Metacognitive activities encourage students to become more self-aware as critical thinkers and problem solvers. When students are aware of their own learning process, their learning is enhanced (Bransford et al., 1999; Lin, 2001). For the purpose of community building, allowing students to collaboratively engage in metacognitive activities provides them with opportunities to practice metacognitive skills together and build shared learning experiences in their academic community. By collectively reflecting on and regulating their own learning process, students learn to think critically and to clearly communicate their thoughts to others.

When would I use metacognitive activities? We encourage you to use metacognitive activities frequently and consistently throughout your course in order to serve students and their learning needs. It is important to not only help students articulate their own thinking but also establish a shared understanding of the goals for metacognitive activities. Therefore, create opportunities early in the course to have a conversation with students about the value and usefulness of metacognitive activities and continue the conversation throughout the course.

Sample activities

| Personal definition of learning |

(Barkley et al., 2014, p. 61) |

| Biographical writing prompts |

(Lohr & Haley, 2018) |

| Goal ranking and matching |

(Angelo & Cross, 1993, as cited in Barkley et al., 2014, pp. 62-63) |

| Group reflection |

(Tanner, 2012) |

| Muddiest point |

(Angelo & Cross, 1993; Tanner, 2012) |

Content-based Activities

What are content-based activities? Content-based activities involve the course’s subject matter. Community building can occur not only through informal, casual interactions but also through discipline-specific conversations in collaboration with peers. By engaging in activities that are geared toward achieving their shared learning objectives, students motivate each other to learn and create a safe learning environment for themselves.

Why would I use content-based activities? What do they achieve? Content-based activities serve the purpose of achieving both community building and content learning objectives of the course. By encouraging students to engage with course content in a collaborative manner with their peers, content-based activities help build a learning community with diverse opportunities for peer-to-peer interactions. Through such peer interactions, students are able to recognize the diversity in perspectives and learn the value of collaboration.

When would I use content-based activities? Content-based activities can occur at any point of the semester as long as they are implemented with clear goals and guidelines: at the beginning of the semester, content-based activities can orient students to the general subject matter; in the middle of an ongoing course project or course unit, they can facilitate student inquiry and learning; and at the end of a major assignment or course unit, they can be used for collaborative reflection.

Sample activities

| Concept-specific soundtrack |

(Dunlap & Lowenthal, 2010, pp. 64-65) |

| Favorite content sharing |

(shared by a member of the Columbia teaching community at the Hybrid & Online Teaching Institute) |

| Course-concept mapping |

(Barkley et al., 2014, p. 63) |

| Search for real-life examples |

(Palloff & Pratt, 2007, p. 167) |

| Resource sharing |

(Palloff & Pratt, 2007, p. 181) |

Considerations for Modality and Class Size

With intentional planning, community building can happen not just in class but also outside of class. If group work is challenging to manage in large classes, some of the community building strategies can be adapted to fit the large class setting. Below is a list of general considerations for different pedagogical contexts.

Asynchronous Modality

- Assign a community building activity to students to complete in their own time.

- Specify the deadline for completion.

- Ask students to share their completed activity in a discussion forum and comment on each other’s post (e.g., discussion boards in CourseWorks, shared Google document or slides)

- Utilize your course’s learning management system (e.g., CourseWorks) to extend the class community to the asynchronous platform. For example, in CourseWorks, consider creating group discussions and arranging regular asynchronous group interactions throughout the semester.

- Regularly check in on students and make sure to maintain your teaching presence. Some strategies include:

- Providing a verbal summary of the community building activity in class.

- Commenting on student posts online.

- Emailing the highlights of the completed community building activity.

Large Courses

- Consider ways to make student interactions more intimate and workload manageable.

- If you ask students to participate in icebreaker activities or other group assignments, consider putting students into the same groups each time so that they have the opportunity to become acquainted with each other in a smaller group setting throughout the semester.

- If you ask students to upload posts in discussion boards in CourseWorks or another online platform and read and comment on each other’s posts, consider creating group discussions so that students are expected to read and engage with only their group members’ posts.

- After an in-class group activity, having every student group report back to the whole class may be too time-consuming if there are too many small groups. The following are some alternative suggestions for the whole-class debrief.

- Rather than having every student group report back, randomly select groups to share their discussions.

- If you ask students to take notes in a collaborative document during their group activity, skim through their notes and highlight some of them by identifying particular emerging themes/patterns and reading them out loud to the whole class.

- If students engage in a problem-solving activity in small groups, quickly assess their learning with a polling tool (e.g., PollEverywhere, Zoom poll).

- Assign students a community building activity in advance so that they can complete it before coming to class. Use Google Forms or other online survey tools to collect their responses. In class, use the survey results to facilitate a whole class discussion. You could also use a polling tool (e.g., PollEverywhere, Zoom poll) to invite students’ participation during class.

References

Adams, B., & Wilson, N. S. (2020). Building Community in Asynchronous Online Higher Education Courses Through Collaborative Annotation. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(2), 250-261.

Ambrose, S. A., Lovett, M., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2011). Assessing metacognition in an online community of inquiry. The Internet and Higher Education, 14(3), 183-190.

Baker, C. (2010). The impact of instructor immediacy and presence for online student affective learning, cognition, and motivation. Journal of Educators Online, 7(1), n1.

Barkley, E. F., Cross, K. P., & Major, C. H. (2014). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Berry, S. (2017). Building community in online doctoral classrooms: Instructor practices that support community. Online Learning, 21(2), 42-63.

Berry, S. (2019). Teaching to Connect: Community-Building Strategies for the Virtual Classroom. Online Learning, 23(1), 164-183.

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., & Cocking, R.R. (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Brown, R. E. (2001). The process of community-building in distance learning classes. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2), 18-35.

Bush, R., Castelli, P., Lowry, P., & Cole, M. (2010). The importance of teaching presence in online and hybrid classrooms. In Proceedings of the Academy of Educational Leadership (Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 7-13).

Chlup, D. T., & Collins, T. E. (2010). Breaking the ice: Using ice-breakers and re-energizers with adult learners. Adult Learning, 21(3-4), 34-39.

Cowan, J. E. (2012). Strategies for developing a community of practice: Nine years of lessons learned in a hybrid technology education master’s program. TechTrends, 56(1), 12-18.

Dunlap, J. C., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2010). Hot for teacher: Using digital music to enhance students’ experience in online courses. TechTrends, 54(4), 58-73.

Dunlosky, J. and Metcalfe, J. (2009). Metacognition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fisher, M., & Tucker, D. (2004). Games online: social icebreakers that orient students to synchronous protocol and team formation. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 32(4), 419-428.

Garrison, D. R. (2009). Communities of inquiry in online learning. In Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, 2nd Edition (pp. 352-355). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2010). The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1-2), 5-9.

Lai, E.R. (2011). Metacognition: A Literature Review. Pearson’s Research Reports.

Lai, K. W. (2015). Knowledge construction in online learning communities: A case study of a doctoral course. Studies in Higher Education, 40(4), 561-579.

Lin, X. (2001). Designing metacognitive activities. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(2), 23-40.

Lohr, K. D., & Haley, K. J. (2018). Using biographical prompts to build community in an online graduate course: An adult learning perspective. Adult Learning, 29(1), 11-19.

McGrath, N., Gregory, S., Farley, H., & Roberts, P. (2014). Tools of the trade: breaking the ice with virtual tools in online learning. In Proceedings of the 31st Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education Conference (ASCILITE 2014) (pp. 470-474). Macquarie University.

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6-23.

Moore, M. G. (1973). Toward a theory of independent learning and teaching. The Journal of Higher Education, 44(9), 661-679.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2007). Building online learning communities: Effective strategies for the virtual classroom. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Rovai, A. P. (2003). In search of higher persistence rates in distance education online programs. The Internet and Higher Education, 6(1), 1-16.

Sadera, W. A., Robertson, J., Song, L., & Midon, M. N. (2009). The role of community in online learning success. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 5(2), 277-284.

Shrivastava, P. (1999). Management classes as online learning communities. Journal of Management Education, 23(6), 691-702.

Tanner, K. D. (2012). Promoting student metacognition. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 11(2), 113-120.

The CTL researches and experiments.

The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning provides an array of resources and tools for instructional activities.