Getting Started with Active Learning

Active learning strategies involve students not just in doing things, but also thinking about what they are doing (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). Intentionally incorporating active learning strategies can benefit student learning (Deslauriers et al., 2019; Freeman et al., 2014; Prince, 2004), and when done inclusively, can also narrow achievement gaps for traditionally underrepresented students (Dewsbury, 2017; Theobald et al., 2020). This resource introduces you to a holistic active learning framework (adapted from Fink, 2013) as well as Columbia-supported instructional technologies that you can use to design both synchronous and asynchronous activities to engage your students in active learning. You can also use the Planning Active Learning Experiences Worksheet (PDF | Google Doc) to plan your own activity to implement in your next class session.

The CTL is here to help!

Seeking additional support with planning for active learning in your course? Email CTLFaculty@columbia.edu to schedule a 1-1 consultation. For support with any of the Columbia tools discussed below, email ColumbiaCTL@columbia.edu or join our virtual office hours.

Interested in inviting the CTL to facilitate a session on this topic for your school, department, or program? Visit our Workshops To Go page for more information.

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2022). Getting Started with Active Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/active-learning-basics/

What is Active Learning?

While the term active learning might appear to encompass any activity that students do as part of their learning process, not every activity qualifies as “active learning.” As Freeman et al. (2014) describe, “Active learning engages students in the process of learning through activities and/or discussion in class, as opposed to passively listening to an expert. It emphasizes higher-order thinking and often involves group work” (pp 8413-8414). This implies that activities such as passively listening during a lecture or class discussion, or copying verbatim what the instructor writes on the board or present on a slide are not considered active learning unless paired with additional activities that get students to further engage and reflect on the material.

Bonwell & Eison (1991) describe active learning as instruction that “involves students in doing things and thinking about the things they are doing” (p. 19). They found that active learning strategies in the college classroom typically:

- Prioritize developing students’ skills over transmitting information to students.

- Engage students in higher-order thinking processes such as analyzing, evaluating, and creating, in addition to recall.

- Involve students in activities such as reading, discussing, and writing, in addition to listening.

- Encourage students to explore their own knowledge, attitudes, and values.

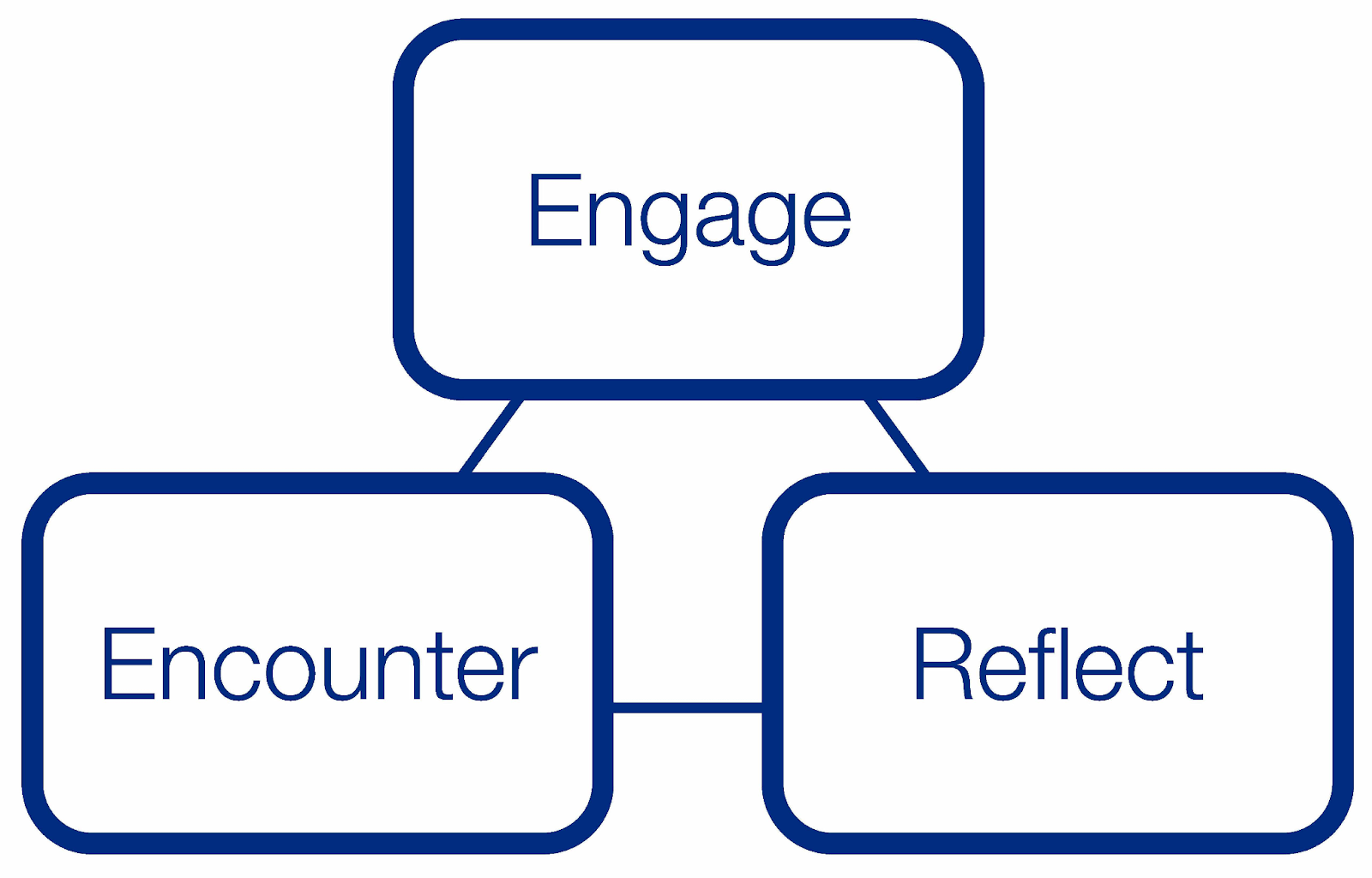

Fink (2013) expanded upon Bonwell and Eison’s definition by describing a holistic view of active learning which the CTL has adapted into the following framework:

Figure 1: Holistic Active Learning Framework adapted from Fink (2013)

This framework can be a helpful tool to consider how your students…

- encounter (new) information and ideas

- engage with information and ideas

- reflect on their learning

…to meet the student learning objective(s) of your course.

Planning Holistic Active Learning Experiences

Before selecting an active learning strategy, you should first consider your student learning objective, or what specific knowledge or skill you want students to learn. The Planning Active Learning Experiences Worksheet (PDF | Google Doc) begins with this step and then walks you through the rest of the process, which is detailed below.

Encounter

Once you have clarified the learning objective, consider the essential information and ideas that students will need to encounter. Students can encounter new knowledge in a variety of formats, including:

- Original sources (e.g., peer-reviewed articles, raw data, interview transcripts)

- Secondary sources (e.g., literature reviews, critiques, data analysis report)

- Lectures or screencasts

- Textbooks

- Multimedia (e.g., videos, podcasts, infographics)

Guiding Questions:

- How will students encounter new information and ideas?

- Will this be done synchronously or asynchronously?

- How much time will students need to complete this?

- How will you gauge students’ understanding of new information and ideas?

Engage

Next, consider how your students can engage with the information and ideas in meaningful ways. These might involve hands-on “doing” experiences, such as programming instructions for a robot or composing a song with specific influences, or observing experiences, such as analyzing a livestream of oral arguments at the US Supreme Court or comparing a stage production and a film of Hamlet. You may find it helpful to deconstruct the ways that practitioners or experts in the field or discipline engage with information and ideas, which typically involve higher-order thinking processes such as applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

Guiding Questions

- How will students engage with information and ideas?

- Will this be done synchronously or asynchronously?

- How much time will students need to complete this?

Reflect

Finally, consider how your students should reflect on their learning. This process encourages students to concretize for themselves what they have learned and what it means for them. Making regular reflection an integral part of the learning process can help students improve their ability to reflect and motivate them to use it for their benefit.

Example reflection prompts include:

- What am I learning and what is its value to me?

- How does what I am learning relate to my other skills, knowledge, and values?

- What have I learned so far? What else do I need to learn?

- Which learning strategies have been helpful? What other strategies should I use?

For reflection prompts that pair well with specific learning activities, refer to Example Metacognitive Reflection Prompts.

Guiding Questions

- How will students reflect on their learning?

- Will this be done synchronously or asynchronously?

- How much time will students need to complete this?

Active Learning Strategies

The active learning strategies you select should serve the course or unit learning objectives for your students. As you learn more about the following active learning strategies, we encourage you to use the Planning Active Learning Experiences Worksheet (PDF | Google Doc) to consider the strategy most conducive to helping your students learn, and how you intend to implement it holistically.

We are also happy to discuss your plan with you; schedule a consultation by emailing us at CTLfaculty@columbia.edu.

Strategy: Pre-Class Videos

Why Pre-Class Videos?

Pre-class videos can support students in learning a small amount of new material before class, thereby allowing you to reallocate valuable in-class time for building upon or delving more deeply into the material. These pre-class videos are typically short videos, and can be instructional (e.g., watching a mini lecture on different types of bird vocalizations) or be an artifact that students do something with (e.g., making observations about the bird vocalizations shown in the video). Either type of video can be made more active by designing opportunities for students to think about what they are watching in the video.

How to Use Pre-Class Videos For Active Learning

- Encounter—Have students watch a short informational video on the topic.

- Engage—Have students answer questions based on the video. These questions can be embedded within the video or listed separately, such as in Poll Everywhere or a CourseWorks (Canvas) quiz.

- Reflect—Ask students to write a paragraph on how they think the video allowed them to explore the topic in ways that they otherwise could not.

Columbia-Supported Tools for Creating Pre-Class Videos

- Panopto – Columbia-supported video platform that allows both instructors and students to create and host videos for sharing. Instructors can also embed interactive elements in videos, such as multiple choice or short answer questions.

- Zoom Recording – Instructors can use Zoom to record short videos locally on their computers.

Columbia Faculty Using Pre-Class Videos

In this video, Professor Caroline Marvin describes her redesign of her Mind, Brain, and Behavior course that incorporates pre-class videos and the audience response system Poll Everywhere to better engage her students and assess their learning. As you watch the video, note how Professor Marvin promoted active learning in both the synchronous and asynchronous spaces. To learn more, read the Q&A with Professor Marvin.

In the next video, Professor Beth Barron describes her redesign of her Foundations of Clinical Medicine tutorials course to better promote asynchronous learning using videos and case studies on online discussion boards, thereby maximizing in-person, hands-on class time. As you watch the video (begin at time 5:24), note how Professor Barron promotes active learning in the asynchronous space.

Relevant Resources

Strategy: Asynchronous Discussions

Why Asynchronous Discussion?

Asynchronous discussions can be an effective low-stakes way for students to encounter, engage with, and reflect on course material. The asynchronous format allows students the time to think more deeply about the discussion prompt as well as read other student postings for additional insights. Student contributions can be used as building blocks for further in-depth discussion during class time.

How to Use Asynchronous Discussions For Active Learning

- Encounter—To have students encounter / identify one or two counter arguments to their own beliefs / posts / etc., ask students to read through their peers’ posts.

- Engage—Have students comment on the counter arguments, using a framework such as the 3CQ model—Compliment, Comment, Connection, and / or Question.

- Reflect—Ask students to share a few key contributions from their peers that have significantly informed and influenced their perspective on the topic, and how that perspective has been enriched as a result.

Columbia-Supported Tools for Asynchronous Discussion

- CourseWorks (Canvas) Discussion Board – Discussion board with traditional customizable settings such as threaded or focused discussions.

- Ed Discussion – Columbia-supported communication, discussion, and Q&A platform with enhanced discussion board features such as live polls, image annotation, and executable code within posts. Ed Discussion is integrated with CourseWorks (Canvas).

Columbia Faculty Using Asynchronous Discussions

In this video, Professor Denise Cruz shares how she used both asynchronous and synchronous discussion opportunities for her students to engage with course material in her large-enrollment introductory Asian American Literature course. As you watch the video (4:45 – 6:45), note the steps Professor Cruz took to make it easy for her students to contribute to discussions, and how she used her students’ asynchronous contributions to enhance the relevance of her synchronous lectures to students.

Relevant Resources

Strategy: Polling

Why Polling?

Polling is a quick, low-stakes strategy for getting students to think about course material. You can ask students a wide variety of poll questions based on what you want them to think about and how you want them to think about it:

- Opinion-based questions can help students practice expressing their opinions and encounter others.

- Peer instruction-type questions can help students practice explaining their rationale and get feedback from a peer.

- Recall-type questions can help students practice retrieving information from memory, which improves long-term retention.

- Reflection-based questions can help students develop their metacognitive skills and refine their learning process.

How to Use Polling for Active Learning

- Encounter—Poll students for their current opinion about a new topic or subject. Share the results so students get a sense of how their views differ or align with their classmates, and perhaps with external populations as well, if so desired. The results of the poll can be used to launch a class activity, such as a discussion or small group work.

- Engage—Ask students to work through a short problem based on material they just learned and share their responses in a poll. This allows students to practice using the material and allows both instructor and students to identify gaps in understanding and to focus further instruction and learning.

- Reflect—Poll students at the end of the class session for their most important takeaway. This gets students to reflect on what they just learned and informs you as to whether students are leaving the class session with what you want them to.

Columbia-Supported Tools for Polling

- Poll Everywhere – Columbia-supported polling platform with advanced polling features such as open-ended responses, clickable images, and competitions.

- Zoom Polling Tool – Multiple-choice poll on a video-conferencing platform

- Ed Discussion Polling Tool – Multiple-choice poll on a discussion board

- CourseWorks (Canvas) Quiz Tool – Ungraded surveys function like a poll

Columbia Faculty Using Polling

In this video, Professor Caroline Marvin shares how she uses Poll Everywhere in her large-enrollment introductory neuroscience course Mind, Brain and Behavior to encourage student engagement with course material during class and assess their learning in real-time. As you watch the video, note how Professor Marvin uses polling to expand who actively participates in class and how she makes use of the poll results to adjust her teaching to meet the needs of her students.

Relevant Resources

Strategy: Pair Work

Why Pair Work?

Pair work allows students to work through more complex course material with peer support and learn from one another. Depending on how you design the activity, pair work could provide students opportunities to verbalize their thought process, encounter a different perspective, receive quick feedback on ideas, and / or connect with a fellow student.

Pair work can be done synchronously in class as well as asynchronously online. Examples of in-class pair work include Think-Pair-Share and Peer Instruction, and can be enhanced using instructional technologies such as polling. Examples of asynchronous pair work include Peer Review and Collaborative Assignments, and can be enhanced using instructional technologies such as collaborative documents.

How to Use Pair Work For Active Learning

- Encounter—Have students share their prior knowledge and experience with a new topic with their partner.

- Engage—Ask students to discuss and solve a problem together, or ask them to share their thought processes with their partner.

- Reflect—Ask students to reflect on and share a couple of insights—about course material, problem solving, collaboration, etc.—that they gained from working with their partner.

Columbia-Supported Tools for Facilitating Pair Work

- Poll Everywhere – Columbia-supported polling platform with advanced polling features such as open-ended responses, clickable images, and competitions.

- CourseWorks (Canvas) – The Peer Review function allows instructors to assign peer reviewers and share an evaluation rubric for a given assignment. For context, this is the student view of Peer Review assignments.

- Google Docs – Collaborative documents with “Add comment” and “Suggest edits” functions

Columbia Faculty Using Pair Work

In this video, Professor Kyle Mandli shares how he used paired group work, paired programming, and open source technologies to engage his students in the course material and encourage them to learn from each other in his Introduction to Numerical Methods course. As you watch the video, note how Professor Mandli capitalized on the different skill sets that students bring to the classroom. To learn more, read the Q&A with Professor Mandli.

Relevant Resources

In this short video, learn more about the think-pair-share technique, as part of the CTL’s “Teaching Talks” initiative.

Strategy: Case Studies

Why Case Studies?

Case studies provide students with opportunities to apply what they are learning in class to real-world scenarios. Case studies can be designed such that students not only carefully examine all the information presented, but also perform additional research or fact-finding to develop credible solutions or recommendations for the case. Case studies that involve complex scenarios could benefit from having students work on the cases in small groups. For an overview of different types of cases and ways you can implement them in your course, refer to Case Method Teaching and Learning.

How to Use Case Studies For Active Learning

- Encounter—Have students read an article or watch a video that informs the case.

- Engage—Have students work in small groups to complete the case by analyzing, interpreting, synthesizing, and generating recommendations or solutions.

- Reflect—Ask students to reflect on how they can be more effective when working on future case studies (e.g., What was the most challenging aspect about solving the case?).

Columbia-Supported Tools for Case Studies

- LionMail Google Suite – Collaborative tools include Google Docs, Sheets, and Slides, and Drive.

- CourseWorks (Canvas) Groups – Collaborative spaces within the course’s CourseWorks (Canvas) site for students to store and share files, start discussions, and send messages.

Columbia Faculty using Case Studies

In this video, Professor Helen de Pinho describes how she used the case method to provide students with opportunities to examine and work through complex public health issues in her Integration of Science and Practice course. As you watch the video, note how Professor de Pinho supports her students throughout the case studies, including setting clear expectations of participation and assessments, and incorporating multiple opportunities for self and group reflections.

In this video, Professor Mary Ann Price shares how she used the case method in her General Physiology course to help her pre-med students learn to apply course concepts to real-world scenarios. As you watch the video, note how Professor Price selected this active learning strategy not only because it gave students opportunities to integrate their physiology knowledge from across multiple courses, but also because it allowed her students to practice the type of learning they would be doing later in their careers. To learn more, read the Q&A with Professor Price.

Relevant Resources

- Case Method Teaching and Learning

- Case Consortium @ Columbia — Collection of multimedia case studies in journalism, public policy, public health, and sustainable development.

- National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science’s Case Studies – Collection of peer-reviewed case studies in science.

Strategy: Self-Assessments

Why Self-Assessments?

Self-assessments can be a powerful strategy to encourage students to evaluate their own work or performance and reflect on their learning process. Self-assessments typically require students to use a set of criteria or rubric to evaluate something they’ve done or created for the course, such as an essay, project, or exam. Students then answer reflection questions that could help them make sense of their current performance, consider the impact of their prior actions, and develop potential next steps to further their learning. Self-assessments are thus a wonderful opportunity for students to build up their metacognitive skills and take on greater responsibility for their own learning.

How to Use Self-Assessments For Active Learning

- Encounter—Give students a rubric that will be used to assess their work or performance, so they know what is important in the course and can focus their learning efforts accordingly.

- Engage—Have students assess the quality of their own work or performance by applying the given rubric.

- Reflect—Have students reflect on the quality of their current work or performance, and consider steps they will take to maintain or raise that quality in the future.

Columbia-Supported Tools for Self-Assessment

- Mediathread – CTL-developed media analysis platform that allows students to perform close analysis of video, audio, and images. Students can work with media from online sources or upload their own, and incorporate curated selections into their multimedia essays and discussions.

- CourseWorks (Canvas) – Instructors can include a rubric when creating assignments.

Columbia Faculty Using Self-Assessments

In this video, Professor Sarah Hansen shares how she used self-assessments for students to critique and reflect on their own technical, design, and collaborative skills in her introductory General Chemistry laboratory course. As you watch the video (9:56 – 11:35), note how Professor Hansen supports her students throughout the self-assessment process, including creating their own rubrics and incorporating multiple opportunities throughout the course for students to practice and refine this process.

Relevant Resources

Next Steps

Now that you have learned the basics of Active Learning and some strategies you can use in your classrooms, here are some possible next steps:

- Set up a consultation (CTLfaculty@columbia.edu) with us to review your Planning Active Learning Experiences Worksheet (PDF | Google Doc)

- Request a Teaching Observation to get feedback on your implementation of your active learning plan

- Apply for the Active Learning Institute to redesign your course for active learning with a supportive community of fellow faculty

- For additional support with implementing active learning online, refer to Active Learning for your Online Classroom: Five Strategies using Zoom

References

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. 1991 ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports. ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education, The George Washington University. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED336049

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201821936. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Dewsbury, B. M. (2017). Context Determines Strategies for ‘Activating’ the Inclusive Classroom. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v18i3.1347

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. John Wiley & Sons.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93, 223–232.

Theobald, E. J., Hill, M. J., Tran, E., Agrawal, S., Arroyo, E. N., Behling, S., Chambwe, N., Cintrón, D. L., Cooper, J. D., Dunster, G., Grummer, J. A., Hennessey, K., Hsiao, J., Iranon, N., Jones, L., Jordt, H., Keller, M., Lacey, M. E., Littlefield, C. E., … Freeman, S. (2020). Active learning narrows achievement gaps for underrepresented students in undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1916903117

The CTL researches and experiments.

The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning provides an array of resources and tools for instructional activities.